Classes and other meetings sometimes have problems in execution. An instructor or leader may arrive unprepared. Students or attendees may check phones or talk among themselves. Discussions that are intended to flow freely sometimes have lulls. Even those who engage may dominate or remain silent. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit and meetings migrated to Zoom, everything got worse.

“We’d taken our same slightly dysfunctional behaviors into a new environment and expected them to work,” said Paul Hills, an experimental psychologist at the University College London. “Actually, they made things even worse.”

Video classes and meetings offer attendees opportunities to learn, exchange ideas, be creative, make decisions and bond. But during the pandemic, many faculty members and students have found that online meetings limit social interactions and extract psychological costs. Now, a research team led by Hills has discovered that hand signals—gestures such as two thumbs up to signal agreement or scratching one’s head to express a desire to ask a question—help mitigate what many know as Zoom fatigue.

Students who use shared hand signals during video classes reported more positive feelings about their classmates and believed they learned more relative to a control group that did not use gestures. A separate group that used emojis instead of hand signals did not report the same positive benefits.

“[Students using hand signals] suddenly realized that there were other real people on the call and that there was a reason to have the video on,” Hills said. “They might actually get some emotional connection with these relative strangers.”

An individual’s brain assesses—often subconsciously—whether others are listening. Reassuring body language delivers desirable dopamine hits, much as likes on social media do. Those cues trigger a positive feedback loop, according to Hills. But when someone attempts to communicate and is left wondering whether others noticed, the reverse happens. The brain signals that the risk-reward trade-off is not good, discouraging more communication efforts.

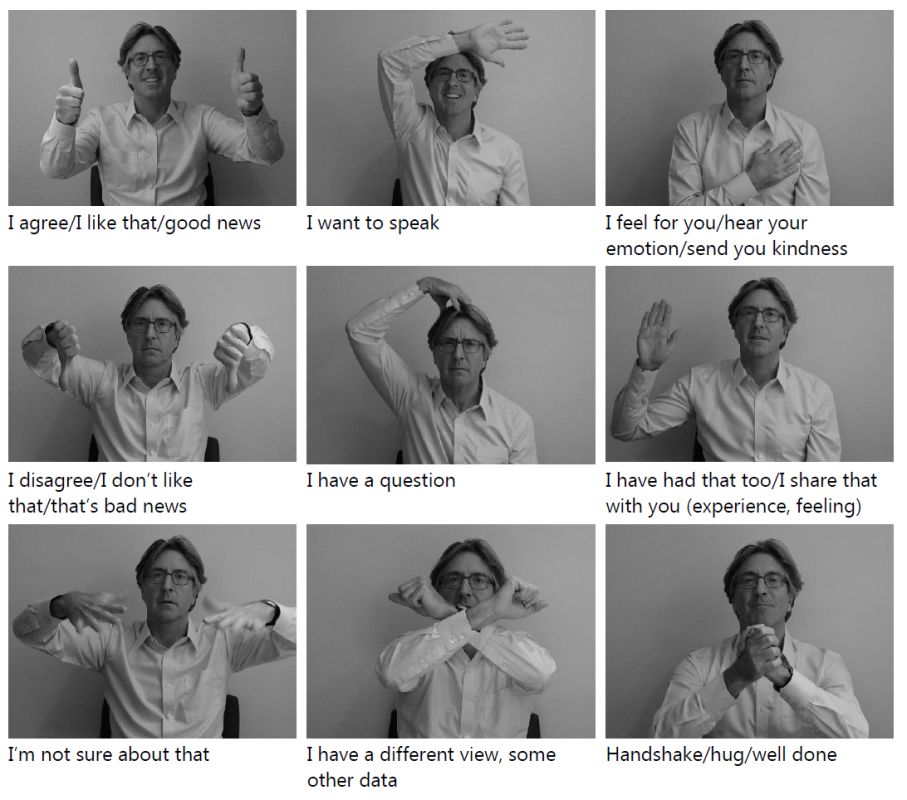

Though videoconferencing appears to mimic in-person interaction, small viewing windows or turned-off cameras often suppress information gleaned from subtle nods, gentle smiles or ever-so-slightly raised eyebrows. To counter this effect, Hills developed a set of adaptable, easy-to-remember and easy-to-interpret gestures intended for spontaneous use during video calls.

Some of the gestures improve transitions between speakers. A wave that uses the entire arm indicates a desire to speak. Arms crossed like an X signal “I have a different view.” Scratching the top of one’s head with all five fingertips means “I have a question.”

Other gestures show connection and emotion. Two thumbs up or down signal agreement or disagreement, respectively. (Both digits are necessary to confirm that one thumb is not busy scrolling on social media.) A hand on heart means “I feel for you.” Outstretched palms that rotate at the wrists signal, “I’m not sure about that.”

Still other gestures help with meeting management. A hand cupped on one’s ear means, “Speak up, please.” Two hands tracing out circles mean “Come to a conclusion.”

“There is value to a standard set and likely to training in how to use physical gestures,” said Dave Miller, assistant teaching professor in the Tufts University mechanical engineering department, who is not affiliated with Hills’s study. “Although perhaps any standard set of gestures, including ones organically developed by a group itself, could be helpful.”

Miller has published research indicating that viewing oneself during videoconferences may elicit negative self-focused attention that contributes to virtual meeting fatigue. Fatigue was higher for women than for men and higher for Asian than for white participants.

Lifeguards have long used hand signals to communicate at great distances. Hills works as a lifeguard on a beach near his home in Cornwall, England, and whenever a fellow lifeguard reciprocates one of his gestures, he feels a stronger bond with that guard and the group. That observation inspired his work investigating hand signals in videoconferencing.

Students in remote classes or faculty members in virtual meetings often do not know when to talk or interrupt. To enhance engagement, productivity and fun in virtual meetings, Hills’s research team has also introduced the notions of “team chairing” and “team passing.” The practice draws parallels to a team captain and players on a soccer field.

To enhance the conversational flow, virtual meeting attendees are encouraged to adopt a team mind-set. That means attendees should show up, participate and be attentive for the whole “game”—or meeting. Individual speakers, instead of falling silent after speaking, should take responsibility for “passing” the conversation, much as soccer players pass the ball on a field. Instead of passing to the instructor (team captain), they might scan the virtual meeting room (field) for classmates (teammates) who are gesturing reasons they hope to be called on (receive the ball).

One classmate might signal that they have a question. Another might signal that they have a different view. Yet another might indicate agreement. Some may not gesture, and that may be acted on, too, as team players often work to include everyone. Once the current speaker makes an explicit decision about which classmate will speak next, the conversation shifts in a way that minimizes delays and enhances the flow.

“Before using the signals … I was always the default person to navigate the discussions, in that the students always passed back to me after they had finished raising their points,” Frey Lygo-Frett, a University College London seminar leader, said in a reflection after participating in the experiment. “Once we had implemented the signals, the students were much more willing to pass the discussion between each other rather than back to me each time.”

Hand signals are designed to elicit high performance from attendees during a short period of time. When an instructor or meeting speaker plans to deliver a long PowerPoint presentation, for example, Hills sees no need for attendees to turn on their cameras.

“The other carrot I dangle is shorter meetings,” Hills said. “Maybe we could have 45-minute meetings instead of one-hour meetings … and have 15 minutes of well-being time.”

from Inside Higher Ed | News https://ift.tt/AJFtmsh

No comments:

Post a Comment