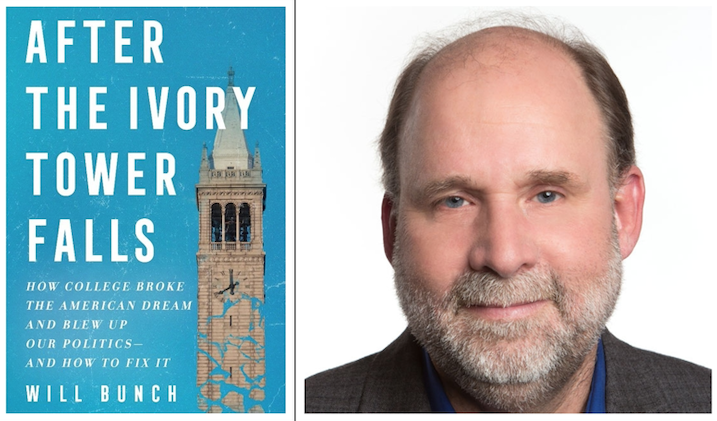

In his new book, After the Ivory Tower Falls: How College Broke the American Dream and Blew Up Our Politics—and How to Fix It (William Morrow), Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Will Bunch, national opinion columnist for The Philadelphia Inquirer, traces the evolution of American higher education since World War II, exploring how it fueled—and was fueled by—the country’s deep political and cultural divides. In a phone interview with Inside Higher Ed, Bunch attributed many of this country’s current travails—from climate change denial to the Jan. 6 insurrection—to “a failure of education.” Excerpts of the conversation follow, edited for length and clarity.

Q: Your book tells the history of modern America through the breakdown of higher education. Where did the trouble begin?

A: The history of college and the modern history of America are more intertwined than people realize. The culture wars in this country really came out of the campus protest culture of the 1960s and how people reacted to [them]. And campus protests were the big thing that propelled Ronald Reagan’s political career, for example … I think the story of America after World War II is the story of a country that suddenly found itself more affluent and realized that knowledge and technology and learning were the key to getting ahead. Because of that understanding, you saw this massive investment during the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s in higher education—in building new dorms and hiring professors; enrollment increased exponentially during those years. Since then, you’ve seen a backlash, driven by the right, in terms of what liberal education does to the minds of our young people. That’s really influenced the way we fund higher education. And that resentment, ultimately, became baked into what’s become the modern conservative movement in this country.

Q: You write that the GI Bill [which provided educational benefits for returning service members] had unintended consequences. What were they?

A: The initial positive, unintended consequence was that it really changed the mind-set of who college is for. For so much of American history, college had really been for a tiny sliver of elites. In the early 1940s, only 5 percent of Americans had a bachelor’s degree. The sense was that most people weren’t college material. There’s a famous quote from the president of the University of Chicago in the 1940s, who said, if we let all these GIs in, our campuses will become “hobo jungles.” And of course, it turned out that these GIs, who were a little more mature than the average student—plus they’d been through this horrific experience of fighting a war—came to college really appreciating the opportunity and eager to learn, and they outperformed the so-called civilians. It made people realize that there was a benefit to the vast middle class of higher education.

The negative unintended consequence is that this era coincided with the heyday of top educators pushing the idea of liberal or general education—that you’re going to college to develop a philosophy of life, to learn how to learn, to develop critical thinking, to become a better citizen. These educators said, “Better-educated citizens will be great for democracy.” And what actually happened was the better-educated citizens realized there were a lot of problems in the way that America was doing democracy, particularly with racial segregation in the ’60s. By the mid- to late ’60s, the focus turned to the Vietnam War. You saw these massive protest movements on campus. And among conservatives who wanted to maintain the status quo, there was obviously a backlash to what was happening in college.

Q: One of the central themes in the book is the tension between liberal education and careerism. How has that played out against the backdrop of partisanship in this country?

A: One of the most dramatic statistics I found was from UCLA, which for decades has done a big national opinion survey of incoming freshmen. One of the things they ask is, basically, what’s the purpose of college? In 1969, 82 percent of freshmen said the main purpose was to develop a meaningful philosophy of life. And by 1985, or 16 years later, that number plunged in half, to like 43 percent. And the top answer that replaced it was to be “very well-off financially.”

You saw this play out in practical ways. Majors in the humanities and social sciences plummeted in the ’70s and ’80s. And business, and other more career-oriented majors, took precedence. There were a couple of things going on there. One is the American economy changed. In the ’60s, when there were jobs available for anybody, it was easy to think that I’m going to college to develop a philosophy of life. By the ’80s, people felt this pressure to learn skills in college that would help them get a good enough career to stay in the middle class. The other thing that changed, starting in the late ’70s, was the arrival of larger-scale student debt. Logically, the more debt that students incur, the more pressure they’re going to feel to get into the kind of job that can pay the loan back.

Q: So who should fund college? Do you believe it’s a public good the government should pay for?

A: I do. For a long time in America, we’ve accepted the idea that educating our children through high school—K through 12—is a public good. As far back as the 1940s, educators and top government officials realized that going beyond 12th grade was going to be necessary to be a successful citizen. The very important but kind of forgotten Truman Commission of 1946–47 [which studied higher education policy] recommended that education should be free through what they called the 14th grade, which today we would call community college or the first couple years of a public college. And that was 75 years ago. Given the changes in the economy since then, I think it’s perfectly rational to say that getting a college diploma or getting other kinds of career training is just as important today as getting a high school diploma was in 1946. And yet, we still treat college as a personalized private good.

The way public goods are determined in society is, what are the benefits? Does all of society benefit by having a better-educated public? To me, that seems like a no-brainer. The economic benefits of having a more educated workforce are clear. And more and more, I think we’re realizing the civic disadvantages of not having a fully educated public, because look at some of the problems we’re encountering today: climate change denial, the huge numbers of the public who are willing to buy into out-there conspiracy theories, like QAnon. Something like Jan. 6, if you really dig down deep inside, is [caused by] a failure of education.

Q: How so?

A: The fact that people had not developed critical thinking skills, that they were prone to manipulation by an authoritarian leader, which Donald Trump essentially was. It’s exactly the opposite of the kind of critical thought that we hoped people would develop by getting a college education, or some type of higher education. One thing I stress in the book is it doesn’t have to be people sitting in a classroom for four years, getting a degree. But I do think we need to rethink how we keep educating our citizens after age 18, instead of just leaving them in the lurch, which is what we do right now.

Q: The Jan. 6 insurrectionists would say you’re doing exactly what they don’t like: being a liberal elite, patronizing them with your culture wars.

A: I think those attitudes have been hardened by the system we’ve developed for higher education over the last 50 years, which many have described as a meritocracy. Back in the golden age of college in the ’50s and ’60s, when we thought a rising tide was lifting all boats, we started promulgating this idea of a meritocracy, that what this new society meant was that you would rise to the level of how far you went in the educational system. And the implication is clear: the more education you have, the more merit you have.

There are a couple of problems with that. One is that over the years, the college system has been reworked and rigged so that people from elite families have all these advantages to stay at the top, whether it’s legacy admissions or the ability to spend thousands of dollars on SAT prep. They have gamed the higher education system to become kind of a permanent, elite class and lock other people out. Yet because we have bought into the myth of meritocracy, you get these attitudes of, “We’re the enlightened ones, because we have this education.” And when you’re talking about Jan. 6, and the feelings of people who are the core of the Donald Trump political movement, that’s the resentment they’ve tapped into.

One of the key points I try to stress in this book is we need to break that cycle of using education to look down on people. That’s why I think there needs to be a radical rethinking of what higher education means. And you’ll notice I’m using the term “higher education” a lot more than “college,” because that’s part of the problem. Think about it: only 37 percent of the American adult population has a bachelor’s degree. About a third have a bachelor’s degree or more, a third have some college and a third, for whatever reason—either aptitude or economics—haven’t set foot on a college campus.

And in this faux meritocracy we’ve developed, the people in that last third absolutely feel they’re being looked down on. They’re dealing with a double whammy. For one thing, the economic system has changed. In the 1950s, you could work in a factory job and make enough money to buy a boat or a vacation cottage or have a couple of cars and a nice life. Today those type of jobs for non–college graduates have dried up. On top of that, they feel the people who did benefit from the system that locked them out are looking down on them. Resentment of that system is inevitable.

Q: So what’s the solution? How can higher ed be fixed?

A: I devote a whole chapter to the idea that we need to make a major policy initiative out of the idea of a gap year for people when they turn 18, which is the key age where we’re losing people. And that’s happening to different people for different reasons. For the people who are doing OK in the educational system and are college bound, they feel so much pressure to get into the right college and make the right career decision when, I know from my own experience—and as somebody who’s raised a couple of kids who are in their late 20s—that the vast majority of kids really don’t know enough yet about what they want to do when they’re 18.

Then we’re seeing more and more that the people who aren’t going to college are kind of dropping off the grid when they hit their late teens. The most extreme example—obviously, you’re talking about a small minority of people—is in the last year or so, we’ve had a flurry of violent mass shootings that were all committed by men in the 18- to 21- or 22-year-old age bracket. But on a more day-to-day level, we’re seeing problems like drug abuse, like the rising suicide rate in that age bracket. I devote a decent chunk of the book to the ideas of the Princeton economists [Anne] Case and [Angus] Deaton, who developed the phrase “deaths of despair.” They’ve monitored people in the primarily white working class, who have much higher rates of suicide and drug overdoses—mainly from opioids—or alcohol-related deaths. What they found is that deaths of despair are increasing among people who are in their 20s or early 30s. And the No. 1 factor that determines if you’re at risk for this is whether you have a college degree.

from Inside Higher Ed | News https://ift.tt/BC715PH

No comments:

Post a Comment