The House and Senate Appropriations Committees have brought back earmarks after a 10-year moratorium, but this time the provisions come with several reforms that could make higher education institutions prime recipients of the funding.

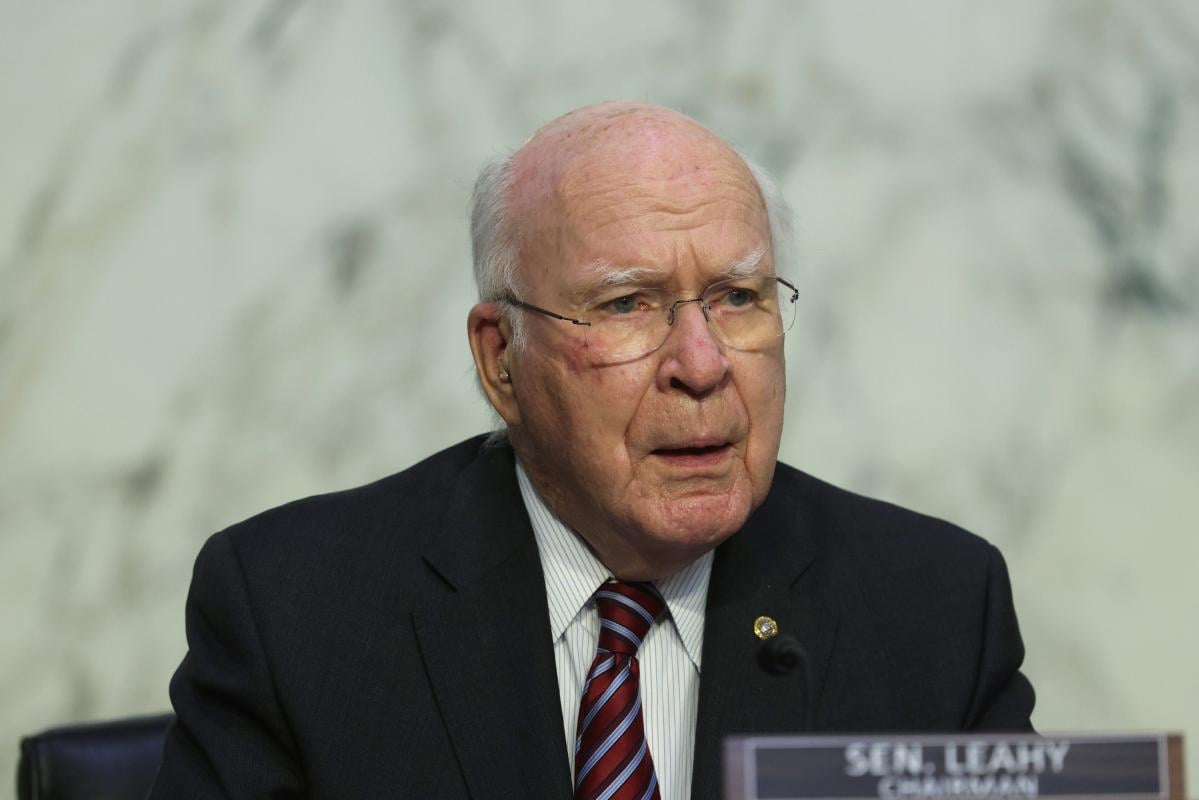

Now referred to as “community project funding” in the House and “congressionally directed spending” in the Senate, earmarking allows lawmakers to direct funding from federal agencies to specific projects in their home states or districts. The practice was controversial, with opponents concerned about corruption and wasteful spending. But with its ban in 2011, Congress ceded some of its power to the executive branch, said Senate Appropriations Committee chair Patrick Leahy, the Democrat from Vermont.

“Even though we appropriate the money, we can't even direct even a tiny fraction of the tax dollars we collect from the hardworking constituents and send those tax dollars back into the communities,” Leahy said in an April 26 floor speech announcing that the committee would begin accepting requests, adding that executive bureaucrats “can’t understand our communities to the extent each one of the 100 senators in this body do.”

One of the past problems with earmarking is that the money was often used to fund projects that weren't in the national interest, said Matthew Dickerson, director of the federal budget center at the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation. Citizens Against Government Waste, an organization seeking to end government mismanagement, created an earmark database to document spending for projects ranging from opera houses to a teapot museum. The most famous example is the "Bridge to Nowhere," in which a ferry in southeast Alaska was planned to be replaced by a $400 million bridge that would serve a small number of people.

"For every Bridge to Nowhere, there's lots of other clear examples of waste," Dickerson said. "That's not something that you want to tax people from around the country and spend it on who can lobby for other people's money."

It's the lobbying and corruption scandals created by earmarking that led to public backlash against the practice, added Dickerson. Four lawmakers were charged with earmark-related corruption crimes from 2005 to 2008, including former representative Randy "Duke" Cunningham, a Republican from California, who accepted $2.4 million in bribes from defense contractors. Lobbyists were also convicted, with the most notable example being Jack Abramoff, who was hired by Native American tribes to secure earmarks that tribal leaders wanted.

"Even if there's not necessarily a felony occurring, there's still a culture of corruption," Dickerson said. "Where there's lots of federal money available that can go to specific entities, there's a lot of incentive for special interests to do unscrupulous things."

Democrats are attempting to curb earmark abuse by introducing reforms: all of the requests must be available online, along with a disclosure stating the lawmaker has no financial interest in the project; the overall funding is limited to no more than 1 percent of discretionary spending; and for-profit entities cannot receive any of the funding. House members are limited to 10 spending requests, but there is no cap for senators.

“The new system that restricts the congressionally directed funding to nonprofit organizations sets institutions up pretty strongly in terms of being competitive as recipients of those grants,” said Jonathan Fansmith, director of government relations at the American Council on Education. “You certainly have the possibility for a lot of support coming back to higher education through this process.”

Higher education received a huge share of earmark spending before it was banned -- over $2 billion per year across hundreds of requests, said Fansmith. And so far, higher education has been well represented among the community projects proposed by House lawmakers, who submitted a total of $5.9 billion in requests.

Most deadlines for requests in the Senate aren’t until June, so requests from senators aren’t yet available.

Among the House requests are $437,000 for Eastern Kentucky University to fund a center for STEM excellence submitted by Republican representative Andy Barr; $1.2 million for California State University, Fullerton, to build a pedestrian bridge, submitted by Republican representative Young Kim; and $1.3 million for the University of Massachusetts at Boston for the initial design and engineering phases of a new nursing and health sciences building submitted by Democratic representative Stephen Lynch.

Traditionally, earmark requests were dominated by universities, but as the number of requests grew prior to the ban, community colleges also began to receive funding for projects on their campuses that couldn’t be supported by other programs, according to David Baime, senior vice president for government relations and policy analysis at the American Association of Community Colleges. That’s expected to continue this time around.

“We were encouraged by the trend of greater community college funding through this route, and we're expecting that our colleges will continue to exercise that opportunity,” Baime said.

Democratic representative Sharice Davids has requested $5 million for a commercial driver training range at Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kan.; Democratic representative Seth Moulton requested $900,000 to renovate the anatomy and physiology lab at North Shore Community College in Danvers, Mass.; and Republican representative Fred Upton has requested $900,000 to enhance distance learning technology at Glen Oaks Community College in Centreville, Mich.

Submitting a request is only the first step -- lawmakers will still have to decide which requests make it into the final appropriations bill. Projects requested by a member of the Appropriations Committee typically have a better chance of receiving funding.

Though higher education has accounted for a considerable portion of earmark spending in the past, the projects funded weren’t the types that led to earmarking’s downfall, said Fansmith.

“By and large, when you look at the ones that made their way to campuses, these were all things that I think most taxpayers would look at and say, ‘That’s a reasonable use of taxpayer money,’” Fansmith said. “We’re not the area where the controversies occurred and we’re not the area where controversies are likely to occur going forward.”

Still, there have been concerns that earmarks for specific research projects at colleges and universities would undercut the process of obtaining funding through peer review -- that institutions wouldn’t have to submit proposals for a grant competition if they could receive funding directly through their congressional representative.

Through the peer-review process, scientific experts evaluate the strength of research project proposals submitted to agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, so that federal funding is given to those of the highest quality and with the best ideas.

The Association of American Universities has spoken out several times over the last 15 years against using earmarks to allocate federal research funding, most recently in 2018.

“AAU has historically maintained that earmarking of federal research funds reduced the capacity of federal agencies to support the most promising research and thereby impaired the quality of their research programs,” the organization said in 2018. “We maintain that specific research grants and awards are best determined by experts based upon merit.”

from Inside Higher Ed | News https://ift.tt/3tVVqoo

No comments:

Post a Comment